The waves are rocking the boat. They rob you of your balance, pushing and pulling up and down. Your body feels the sea’s movement. It has to react to it, to counteract the force or to go with it. It really depends on what you are planning on doing right now, right here, in the middle of the ocean. The stars look like diamonds studded in the darkness above and around you. Underneath you is the water, filling the Atlantic basin. You are floating above mountains, above an unknown world. Occasionally creatures from beneath break through the surface of the water. Dolphins swim alongside you. The song of whales is the only thing you hear.

Published in October 2020 in Point.51 – Issue 03

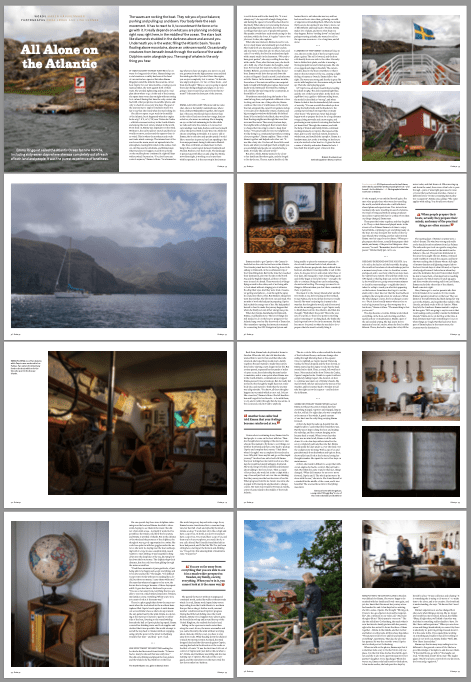

It goes against human nature to be on water for long periods of time. Human beings are social creatures: sociality has been at the heart of our survival as a species. But when Emma Ringqvist sailed the Atlantic Ocean alone on her boat Caprice for over nine months, covering 15,000 nautical miles, she went against both of these traits. She avoided sightseeing and made no real plan about where to go. At the end of the journey, she spent sixty-seven days straight without setting foot on land. During that time the only contact she had with other people was via satellite phone, and only to check in once every few days. The goal of the journey was to explore loneliness itself. It is fair to say that she found what she was looking for.

Emma did not expect to get stuck in the middle of the Atlantic, but it happened when her engine broke at 37° 6’ S, 12° 17’ W, near Tristan da Cunha – a British overseas territory in the South Atlantic and among the most remote islands in the world. From then on, Emma was dependent on the wind. Without it, the sail would not stretch and the boat would not move, and around the equator there is no wind. This is where the northeast and south-east trade winds converge. The intense heat of the sun forces the warm, moist air upwards into the atmosphere, leaving little wind on the surface. Sailors call this area the doldrums, and Emma knew what was about to happen. A call from a friend on the satellite phone confirmed it: eight full days without wind. Frustration. “You don’t have any control anymore,” Emma told me. “As a human being, when you have an engine, you turn it on, and you get away from the high-pressure area and find the wind again. But if you don’t have the engine, you are just completely lost to nature.” At first she was angry and upset – for two or three hours – and then she thought: “Okay, so are you going to spend these days being unhappy and angry, or are you going to learn to just let go and to be in this moment?” It became the best part of the journey.

■

Emma laughs a lot. When we talk via video chat, she is at her family’s summerhouse where they celebrate Midsummer together, the longest day of the year. Her blonde hair is shorter than in the videos I had seen from her voyage, but just as before, she wears no makeup. She is keeping an eye on the kids swimming in the lake while we talk, and turns the camera so I can see her surroundings: reed beds, bushes, and trees beneath a blue sky spotted with clouds. Once in a while she shouts something in Swedish. It is easy to talk to Emma; she is reflective and speaks openly. I would like to meet her in person, but I am speaking to her from my apartment during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Madrid.

She lives on Brännö, an island near Gothenburg in the coastal region between Denmark and Sweden. Bushes cover sleek rocks. The landscape is picturesque with blue sea and a big sky. Emma, now thirty-eight, is working on a house there with her partner. It is the next step in her journey: to settle down and live the family life. “It is not always easy”, she says with a laugh. Being alone and having the space for herself has been hard to find lately. When she is not renovating the house and spending time with family, she works in an ecovillage that takes care of people with autism. She spends a week there each month caring for the residents, which she loves. A “regular” nine-to-five job is not for her, she explains.

When she was nineteen, Emma moved to London to study music and eventually got stuck there. She found work as a musician, a guitar teacher, and in a music venue; but also in offices, bars, and cafes. For a while, she lived in an abandoned pub with a music studio in the basement. “We used to have great parties”, she says, recalling those days with a smile. Then, after thirteen years, she decided to fulfil one of her dreams: she bought a canal boat. For her last five years in London, she lived on the Miss Behavin, a seventeen-metre blue houseboat. Emma would drive her up and down the section of Regent’s Canal in north London known as Little Venice. In the warmer summer months, the surface of the water would become carpeted bank-to-bank with bright green algae. Swans and ducks would swim past the windows, making it feel a bit like she was living in the countryside, in the middle of London.

Houseboats extended along the banks of the canal in long lines, each painted a different colour. Looking out from one of the portholes, Emma could see the rows of townhouses on the streets that run alongside the canal. Front gardens led up to wooden doors flanked by ornate columns, and big rectangular windows held family life behind them. If those inside looked back, they would see their floating neighbours through the trees that surround the water. Then every fourteen days, the neighbourhood changed. Boat tenants have to change their mooring in order to keep their licence. “You practically choose your neighbours. It’s like living in a community but without owning a house together”, Emma explains. They cooked dinner together and helped each other out. “It was like a fairy tale. You have all those little canal boats, and when you walk past them at night, you see candlelight and people sat outside having a drink. It’s really like a dream world.”

But after a while, Emma wanted to be closer to her family and brothers again, and she longed to live by the sea. The sea runs in her blood. She learned how to sail when she was ten, and has had several boats since then, gathering a wealth of experience in handling them. When she turned thirty-seven, she decided it was time to move out of Miss Behavin and head back to Sweden. Emma makes lots of plans, and more often than not, they happen. Before “settling down” on land and perhaps starting a family, she wanted to sail on the open sea once more – for a long time, and all alone.

■

I looked at the videos on Emma’s blog. In one, she sits on the deck of her boat Caprice and plays a guitar. The sail is lowered, and the boat rolls heavily from one side to the other. Her salty hair is divided into plaits, and she is wearing a Norwegian pullover and rolled-up jeans. She sits cross-legged and sings in Swedish. The camera is stable, fixed to the boat somewhere so that it mirrors the movement of the sea, creating a slight feeling of nausea as I watch. Emma falls to her right. The waves are strong and the sky is grey. She snorts with laughter into the camera and gets back up. Then she starts playing again.

S/Y Caprice is a 9.8-meter Laurin Koster sailing boat built in 1969. The deck is painted light blue, and the rest of the boat in white. In the book 700 segelbåtar i test, a guide to different sailing boats, the model is described as “strong”, and when Emma looked at her she immediately felt a sense of security. “You can see with the naked eye how strong the hull is built, and the brackets to the casting star feel much stronger than on many other boats.” The previous owner had already begun work to prepare the boat for a long-distance voyage, fitting new sails and a new engine, and purchasing a new system for steering that had not yet been fitted. Through the summer, and with the help of friends and family, Emma continued working intensely on Caprice. She inspected the mast, put in a new electrical system, mounted a windscreen, and installed the autopilot. Emma is a handywoman: just as she is working on her house now, she worked on her boat too. It gives the boat a sense of identity and makes Emma feel safe. I have built this myself; a part of me is in this.

Emma needed to get Caprice to the Canary Islands before she could set sail across the Atlantic. Two friends joined her for the first leg, from Gothenburg to Falmouth on the southwestern tip of the United Kingdom. But by the time they reached their destination, after two weeks on the North Sea and the English Channel, all three of them were in need of a break. They were tired of things flying around in the cabin, and of not being able to look ahead without stinging jets of saltwater flooding their eyes. And they were tired of seawater getting everywhere – even through the spray hood and into their coffee. But Emma’s exhaustion went beyond that. She felt worn out and weak. The months of work she had put in preparing Caprice had sucked the energy out of her. She had pushed herself so hard to make the journey happen that when she finally set sail, all her energy was gone.

When her friends disembarked in Falmouth, Emma could hardly move. The list of things she still needed to do on the boat to prepare for the Atlantic hung over her like the sword of Damocles. She remembers opening the instruction manual for connecting the GPS Navigation System and being unable to piece the sentences together. So she closed it and went back to bed, where she stayed. She knows people who have suffered from burnout, and knew it was impossible to sail in this state. So she gave in to it and rested. After three or four days, she managed to start doing things again and slowly began to feel a bit better – enough to be able to continue. Being alone can be exhausting, she writes in her blog. The energy you need to do things is different when you don’t have somebody there to push you.

She made it to the Canary Islands after another two weeks at sea, before facing another setback. In Las Palmas, she noticed that she was not really herself. She wasn’t enjoying the journey in the way that she thought she would, and felt stressed about the mounting pressure to get Caprice ready to finally head out into the Atlantic. And then she thought, “Well what’s the point? This is the journey of your life, so there is no point in stressing and not enjoying it.” Looking back, she thinks she had forgotten how to live in the moment. She had become so focussed on what she needed to do to prepare that she wasn’t actually living it.

So she stopped, to try and find herself again. She met other people there who were also travelling the world, and with whom she could talk about shared plans and expectations. Two sisters from Germany who were travelling in search of alternative ways of living and without using aeroplanes moved into Caprice with her for a while. From then on, things changed, Emma says.

The three women spent their time together, and they laughed a lot. They cooked dinner and played music in the streets of Las Palmas. Emma took time to enjoy herself while continuing to get everything ready on the boat. In total, she spent five weeks on the Canary Islands. One evening, another sailor invited Emma onto his cargo boat for dinner. “When people prepare their boats, actually they prepare their minds, and many of the practical things are often excuses,” he said. “Remember, boats float and time passes.” Emma finally put out to sea.

■

Emma’s days depended on the nights. As a solo sailor, she had to sail the boat while sleeping. She would set her alarm clock and wake up just for a moment every hour or two to check her course and speed, and to see if any other boats were nearby. Caprice has a system on board that sends out a GPS signal so that big ships can see her. Without it, she would have to get up every twenty minutes to check her surroundings – roughly the time it takes for a ship to reach you after first appearing on the horizon. Sometimes she forgot to set the alarm only to later discover that the boat had been sailing in the wrong direction for six hours. When the wind changes course, the boat changes course too. “But it doesn’t really matter when you’re on such a big journey if you go the wrong way for a few hours,” Emma told me. “The main thing is that you’re safe.”

The days became a routine. Emma would check everything on the boat each morning, and then spend an hour on maintenance. Maybe a part of the sail needed sewing. She had learnt how to maintain a boat in London, when she lived on Miss Behavin. There, she had to empty the toilet, fill the water tanks, and find firewood. When moving up and down the canal, there were often locks to pass through – pairs of watertight gates used to raise or lower the boat between stretches of water at different levels. “A time consuming but meditative occupation”, Emma says, adding: “The same applies with sailing. You should never hurry.”

“When people prepare their boats, actually they prepare their minds, and many of the practical things are often excuses.”

The opening days of Emma’s journey were a sailor’s dream. The wind was strong and stable as she headed south-southwest from Las Palmas. The sails and ropes took on a gentle orange hue, coloured by sand carried on the wind from the Sahara to the east. The particles shimmered in the air as they caught the sun. Emma continued south-southwest towards the equator, and knew she was reaching the doldrums when a full night of intense thunder and lightning erupted above the boat. Several days of calm followed, as Caprice slowly edged forward. Sailors know when they enter the doldrums; they don’t know when they’ll be able to leave them. A few days before reaching the equator, the winds started to pick up again, and three weeks after setting sail from Las Palmas, Emma reached the other side of the Atlantic. Brazil appeared on the horizon.

Here, Emma got to see her parents who flew in from Sweden for a vacation. For two weeks Emma’s parents joined her on the boat. They ate dinner at the table Emma had built during her trip across the Atlantic, and together they sailed to Ilha Grande, an island south of Rio de Janeiro. When they left, the loneliness Emma wanted to explore hit her again. “All I am going to say for now is that I am heading south, possibly towards the Falkland Islands,” Emma wrote on her blog at the time. A final destination provides something to focus on when things are tough. But that had never been part of Emma’s plan: in the truest sense, the journey was the destination.

Back then, Emma had a boyfriend at home in Sweden. When she left, she told him that she wanted him to wait for her, and that when she returned, she hoped they would start a family together. She just wanted to make this journey first, before starting a new chapter in her life. But as time passed, separated by thousands of miles of open ocean, the relationship became harder to maintain, and at some point when Emma was in the South Atlantic, communication stopped. Emma guessed it was a break-up. But she really did not know. She thought he might have met somebody else, and started to think that the journey was a big mistake. “You know, all these thoughts happen in your mind which are not real. It’s just like a reaction,” Emma told me. She felt heartbroken and longed for her friends – to be with them, to cry, and to talk it through. But she was alone on the ocean and could not talk to anybody.

“Another lone sailor had told Emma that your feelings become reinforced at sea”

Unsure about continuing alone, Emma tried to find people to come on the boat with her. Then she thought about stopping at the Azores to take a break. She wanted to fly home to sort things out with her boyfriend and then come back to pick up Caprice and complete her journey. “I had times when I thought I was a complete idiot and such a loser. Why did I leave my life and go on this stupid journey?” Another lone sailor had told Emma that your feelings become reinforced at sea. One day she would feel deeply unhappy, frustrated. She would long for home endlessly and fantasize about talking to her loved ones. Then a couple of hours later, she would sit in the cockpit with a cup of tea and just look out over the sea thinking that the journey was the best decision of her life. When progress from Rio de Janeiro was slow, she stopped in Florianópolis and decided to change course. Her next stop would be Tristan da Cunha, a tiny volcanic island in the middle of the South Atlantic.

The air cooled a little as she reached the borders of the Southern Ocean, a welcome change after sailing through blistering heat at the equator. Close to nightfall, as Caprice neared Tristan da Cunha, the wind dropped and the boat slowed, so Emma started up the engine to take her the final stretch before dark. Then, a sound, followed by si- lence. Nine nautical miles from Tristan da Cunha, Caprice’s engine broke. Unable to repair it without completely taking it apart, the decision on how to continue was taken out of Emma’s hands. She was left with only her sails and at the mercy of the weather, and her journey back to Sweden would take her right across the equator – and back into the doldrums.

■

Good southeast trade winds carried Emma north past Ascension Island, but then everything stopped. Caprice’s sails flapped, limp in the hot, still air. For eight days, she was completely at the mercy of the winds. A gentle current of one knot was the only thing carrying Emma forward.

At first she kept the sails up, hopeful that she might be able to catch what little wind there was. But the waves kept rocking the boat and making the sails flap, and the constant banging noise became hard to stand. When it was clear that there was no wind at all, Emma took the sails down. It took a few days without wind for the sea to completely calm and become flat. Emma would spend the days under a cover she fixed over the cockpit every morning. With a cup of tea and pancakes made from buckwheat and tapioca flour, she would sit and look at the horizon, letting her thoughts wander. She spent the rest of her days on maintenance.

At first, she found it difficult to accept that without an engine she had no control. She just had to wait. But when she came round to that fact, things changed. “What did it matter for us not to move forward, Caprice and I. The whole point was to be alone with the sea,” she wrote. She found herself at a standstill in the middle of the ocean, and it was beautiful. The sea was like a mirror. Everything was silent.

On one special day, there were dolphins swimming near the boat and Emma decided to take a swim, hoping to see them in the water. She did not often swim at sea – normally it would not be possible as the winds could blow the boat away, and Emma is terrified of sharks. But in the absence of the wind and the presence of the dolphins, she thought it was a good opportunity for a swim. She could see quite far with her goggles under the wa- ter so she went in, staying near the boat and keep- ing hold of a rope in case a sudden wind caused Caprice to start drifting. It was beautiful looking down into the deep blue of the sea, knowing how far down the bottom was. The dolphins kept their distance, but she could see them gliding through the water around her.

“I had these moments of pure gratitude, of just being able to be happy and accept everything, and to be alive and just be.” She laughs. “It is difficult to put it into words without it sounding like a cli- ché, but those moments, I carry them within me.” She says that whatever happens to her now, she knows she is stronger because of those days spent adrift. It gave her time to think and to process. “You are so far away from everything that you are able to see it in a much wider perspective. Sweden, my family, society, everything. When you’re in it, you cannot look at it the same way.”

There is a photograph that shows the exact moment when the trade winds in the northern hemisphere filled Caprice’s sails again. A smile beams out across Emma’s face as she looks up towards the sail, pulled taut by the wind. Emma stood staring at the water as it started to pass by on either side of the boat, listening to the sound swirling beneath the hull as Caprice picked up speed. Emma counted her drinking water and food supplies and decided that it was possible. She would attempt to sail all the way back to Sweden without stopping, using only the power of the wind. Gothenburg would be her next – and final – port of call.

Emma spent most of her time reading the books she had borrowed from friends. “I’d never had so many books and that was really nice.” She did some filming and played the four guitars and the Ukulele she had with her on the boat. She would sing every day and write songs. Soon, Emma became transformed into a seasoned captain, her hair full of salt and styled by the wind: a female sea dog. “I would just sit in the cockpit and have a cup of tea. At home, you don’t sit and just have a cup of tea. You sit and have a cup of tea, and then you look at your phone, you read a book, or you call a friend. But I literally found that half an hour had passed, and I’d be like ‘Oh! I’ve just been sitting here, starring at the horizon and drinking tea.’ You get into this amazing kind of meditative state. You just be.”

“You are so far away from everything that you are able to see it in a much wieder perspective. Sweden, my family, society, everything. When you’re in it, you cannot look at it the same way.”

She passed the Azores without stopping and continued north, carried by stable northeast trade winds. In total, Emma would spend sixty-seven days sailing from the South Atlantic to northern Europe. But as she got further north, unusual weather conditions slowed Caprice’s progress. Having had little luck fishing since the South Atlantic, Emma’s food supplies were almost gone. As she sailed north up and around the top of the United Kingdom, she realised she had to land.

Sailing on the open sea is much easier than along the coast. At sea, the waves are smaller and you can be blown by the wind without worrying about obstacles. On the coast, you have to stay away from rocks. While heading down the channel towards Stornoway town in Scotland, the wind dropped dead and the tide turned against Caprice, carrying her back in the direction of the rocks on the Butt of Lewis. “It was the first time I felt out of control of Caprice and I just did not know what to do”, Emma said. Darkness was falling and she was running out of options. She radioed the coastguard, and the next afternoon she was towed the last eleven miles into harbour.

■

Readjusting to live on land in Sweden was difficult for Emma. She was so happy to be reunited with her family and loved ones again, and yet also knew that this meant her journey at sea had reached its end. A few days before arriving, she felt a sense of panic. She thought “Oh my god, I have to be a good person now and be responsi- ble”, she confessed on our video call. “And I also thought: Oh no! This journey is over now.” The day she sailed into Gothenburg, she made what is now her favorite family picture with her parents, right after her arrival. It shows the three of them together – Emma in the middle, and her mother and father on either side. All three have big smiles. “The picture is full of love and life and sums up everything”, says Emma. That day, she also met her partner. He was the one who towed Caprice into her final port at Gothenburg.

When we talk on the phone, Emma says that it sometimes feels scary to live her life in only one place. It is the first time she has lived with a partner, and she is also now a part-time-parent to her partner’s daughter. It is a big change. When she was at sea, Emma only had herself to think about. A few weeks earlier, she had spent five days by herself in a hut. “It was really nice and relaxing.” It is something she is trying to do more of – to make time to be alone, and to be creative. Her boyfriend is understanding, she says. “He knows that I need space.”

Emma’s experience at sea has changed how she reacts when things go wrong. She no longer lets herself become stressed. Instead, she thinks: “Okay, all right then, we’ll think of another way. And that is something really valuable to have. It’s like I have endless patience.” When you are alone at sea and things break which you cannot fix, there is absolutely no point in getting stressed about it. It is the same in life. If you spend time working on something and realise it was all for nothing or plans do not work out, Emma thinks: “Well, OK. Now I have learned that.”

Emma says that in many ways sailing is not so different to the general course of life. She has a good knowledge of metaphors, and she uses them. “If the wind blows, go with it.” She laughs out loud. “If the wind doesn’t blow, stay.” She laughs again. “And if you have a storm from one direction, don’t try and go against it.”

■■

Maren Häußermann

Du muss angemeldet sein, um einen Kommentar zu veröffentlichen.